These are the last three books I have read in 2017, a very satisfying year when it comes to reading. I am not sure how I have managed to find the time, but hope that a less crazy 2018 might mean even more reading time!

A Midwife’s Story – Penny Armstrong & Sheryl Feldman

A Midwife’s Story – Penny Armstrong & Sheryl Feldman

In this memoir of midwifery among the Amish community, Penny Armstrong reflects on her growth and development as a midwife. It’s fascinating to see her confidence in straightforward birth in a home environment increase through experience. She is well-placed to make the comparison with hospital birth in the 1970s, and it is horrifying to note how little has changed. The vignettes of Amish life are also charming, and this is a well-written memoir – certainly the best story of midwifery I’ve read, thanks to writer Sheryl Feldman’s well-judged turn of phrase. I found it utterly absorbing.

[Disclosure: Pinter & Martin sent me a free review copy of this book; you can get a 10% discount on your copy if you use the offer code SPROGCAST at checkout on their website.]

How To Have A Baby – Natalie Meddings

How To Have A Baby – Natalie Meddings

How To Have A Baby is a doula in a book. It’s nearly a big enough book to fit in an actual doula, and crammed with wisdom (just the “big necessaries,” writes Natalie Meddings) sourced from her own experience and the stories of many mothers. Meddings’ tone, like the ideal doula, is firm but gentle, calm and encouraging.

The book takes the expectant mother through the usual route of pregnancy and planning, into labour, birth and the unexpected, and out the other side to feeding and newborn days. Descriptions are clear and “tips and tricks” are shared helpfully at every stage. Meddings is pragmatic and honest. Birth is discussed in terms of an involuntary bodily function, and how to create the optimal conditions for this to happen. Induction is presented as “a ticket on the intervention rollercoaster” (p116) which is an interesting choice of words, however the pages explaining induction are practical and compassionate, giving a clear idea of what happens and what can help.

This book is an excellent resource for birth planning. Meddings is very concerned with consent and human rights, both of which she covers very clearly; and this is her real strength. I much prefer these well-referenced and forthright pages, to the liberal sprinkling of homeopathy etc alongside the useful coping suggestions.

You are waiting to hear what I think of the breastfeeding information, so I won’t keep you in any more suspense. With contributions from Maddie McMahon, the importance of early feeding and skin to skin is discussed, and Meddings describes the newborn feeding reflexes and how to support the baby to self-attach. It is a little surprising when she goes on to describe a rather prescriptive way to hold the baby, which does not support those reflexes so well, given her let-nature-take-its-course-and-things-will-work approach to other aspects of birth and parenting. And sound the klaxon for “breastfeeding granola,” which looks delicious but should correctly be termed “granola,” given that breastfeeding experience is not generally influenced by the consumption of roasted oats and nuts and so on.

Matters are redeemed by the rest of the new-baby/new-mother section, referencing such respected authors as Naomi Stadlen and Deborah Jackson, and with plenty of exhortations to eat cake.

I think this book is jam-packed with stuff that would be useful during labour and birth, and it would set up a new mother nicely for those early days and beyond. Practically speaking, the book is probably a bit too chunky to carry around with you and make notes in, as Meddings suggests in the beginning; in fact I think it would work brilliantly as a loose-leaf binder (or perhaps an app), so the reader can pull out relevant sections as needed (which would facilitate reading whilst feeding). Some websites and numbers are given to access support but there could be a lot more of this. On the whole a very highly recommended book for practitioners and parents-to-be alike.

[Disclosure: Natalie sent me a free copy of her book to review – thank you!]

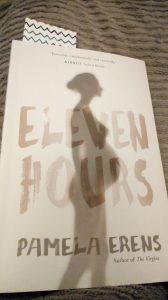

Eleven Hours – Pamela Erens

The last book I finished reading this year was perfect to follow these two, and I think I may even have bought it myself. In Eleven Hours, Lore is in labour, cared for by Franckline who is also in the early stages of pregnancy. As Lore’s contractions come and go, we learn both women’s sad stories: Franckline’s lost babies, and Lore’s lost love. Franckline’s midwifery is full of empathy and kindness, but this is starkly framed by the harsh restrictions and requirements of hospital policy, and the insensitive words and actions of her colleagues.

Lore arrives in the maternity ward alone, with a five page birth plan. Franckline is the only one to read and respect this, and does her best to steer things back towards Lore’s wishes, even as events keep on sliding off track. The labour progresses slowly, and then takes an unpredictable turn. Gripping fiction, and a great way to wrap up Meddings and Armstrong, and 2017.