I am a white, middle class, cisgendered, able-bodied, educated woman in my 50s. I’m part of some marginalised groups but I pass for a straight cis woman and feel my privilege in that; this is a position of relative power, and it is a position reflected in so much of the subject matter of my blog and my podcast, and so many of my guests. I reach out over and over again to my own community, and it’s time to stretch further and learn more. This is a work in progress because I am working out how to be an ally to marginalised communities, how and when to use inclusive language, and how to include one community without alienating another.

As a feminist, I’ve felt particularly challenged by the idea of transgender. I certainly started from a place of suspicion and fear, which felt deeply uncomfortable because I think of myself as a kind, inclusive sort of person, and I could see myself not being that. I couldn’t sit with this level of incongruence, and knew I had to work it out. I was confused by the loud voices on both sides of a deep and dangerous divide. It took me too long to stop listening and start learning. I’m going to list below the resources that helped me, but I want to particularly highlight two things.

Firstly a real threshold concept for me. I attended a Queer Birth Workshop, and the question was asked, what makes you a woman? How do you know you are a woman? I’ve been trying to unravel this for quite some time, having been railing against the gender binary for a decade or more, certain that I didn’t wish to be defined by my biology, or assumed to be delighted by pink unicorns. The logic in my head was that transgender must require an adeherence to strict gender norms, otherwise how could you know you were *not* one thing but another? Letting go of this logic has been massively helpful. During the Queer Birth Workshop, AJ Silver answered their own question: you know it in every fibre of your being. There’s my lightbulb. All the things I had been reading and listening to suddenly made sense. Every fibre of your being. Transwomen are people who feel like a woman in every fibre of their being, and my feminist objections are simply no longer valid. I was recently asked, how can someone in a male body understand what it feels like to be a woman? This too is something I struggled to understand: how can you know what it feels like to be a woman if you’ve never had your period start just before a PE lesson? If you’ve never walked home in the dark with your keys in your hand in case of attack? If you’ve never experienced the pure joy of discovering that a dress has pockets. There is more than one way to be a woman, and none of us gets to decide that our own experience is the defining one.

This came alongside a second thing which was less of an instant epiphany and more of a slow dawning. In another workshop (this one on neurodiversity) there was discussion of a spectrum as being not so much a scale from light to dark, but ALL the colours. No good/bad, no right/wrong, no broken/whole, but all the degrees and all the subsets of degrees and all the branches off all the branches…. this breadth and fluidity is what gender is to me, and having let go of the idea that transgender presupposes a binary either/or thing, it all just slots together.

I don’t believe that I have figured everything out and now know the answer, but I do believe that uncertainty is good for me, good for everyone really to keep on questioning and reflecting. And there isn’t one answer. There are still questions for me around things like sports where maybe the men’s/women’s model needs a rethink for our modern times. And I’m not here to try to persuade you, if your thinking is not currently aligned with mine; but I’m always willing to have a conversation with you.

When it comes to being an ally to people of colour, obviously there is less of a philosophical hoop to jump through; but there is a huge amount of work for someone like me, raised in small northern towns where there were no non-white people around me at all; I had no concept of the microaggressions and the deeply embedded structural racism that affects the way I think, the way I act, and the way I speak to people. There were two conversations I had when making Sprogcast that were particularly instructive, one with Alana Apfel and one with Mars Lord; but what I took away more than anything else was that it was on me to do the work.

My pledge is that I will never stop doing the work.

Most importantly, this needs not to be a zero sum game. At the moment it feels as though everyone has to pick a side; and ironically, using inclusive language makes some people feel excluded. This conversation has to be had, and retreating into our corners and yelling at each other will not move us forward.

Here are some resources, in no particular order:

My non-binary life (podcast)

In the darkroom, by Susan Faludi (book)

The Argonauts, by Maggie Nelson (book)

Queer Birth Club: LGBT+ Competency Birth & Beyond (workshop)

Slay In Your Lane, by Yomi Adegoke and Elizabeth Uviebinené (I read the book, but here’s a link to their podcast)

Queenie, by Candice Carty-Williams (book)

I am not your baby mother, by Candice Braithwaite (book)

Why I’m no longer talking to white people about race, by Reni Eddo-Lodge (book)

Feel Good (TV programme)

Small Axe (TV programme)

The Safe Zone Project (website)

Responding to JK Rowling’s Essay/Is it anti-trans? by Jammidodger (youtube video)

Meet the feminists championing trans rights (Buzzfeed article)

Seahorse (film)

Pride & Joy, A Guide for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Trans Parents, by Sarah & Rachel Hagger-Holt (book)

Birth work as care work, by Alana Apfel (book)

Mars Lord on Sprogcast (podcast, link to follow)

Jones E, Lattof SR, Coast E. Interventions to provide culturally-appropriate maternity care services: factors affecting implementation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):267 (journal article)

Pedagogy of the oppressed, by Paulo Freire (book)

Peace and Power, by Wheeler, C. E., & Chinn, P. L. (1984) (book)

Dear White People (TV programme)

Atypical (TV Programme)

Shitt’s Creek (TV Programme)

It’s A Sin (TV Programme)

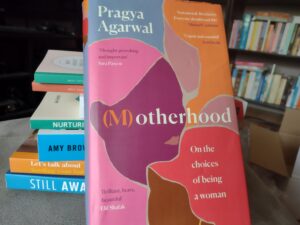

Sway, by Pragya Agarwal (book)

In a note at the end of the book, Pragya Agarwal accurately describes this work as “somewhere between a memoir and a scientific and historical disquisition of women’s reproductive choices and infertility.” (p343) Throughout the book she wanders, with intent, between her own reflections and experiences, and a huge breadth of culture, history, and contemporary research, to explore the massive topic of motherhood and choice, and to wrestle with the impossible definition of woman, and its relationship to motherhood.

In a note at the end of the book, Pragya Agarwal accurately describes this work as “somewhere between a memoir and a scientific and historical disquisition of women’s reproductive choices and infertility.” (p343) Throughout the book she wanders, with intent, between her own reflections and experiences, and a huge breadth of culture, history, and contemporary research, to explore the massive topic of motherhood and choice, and to wrestle with the impossible definition of woman, and its relationship to motherhood.