Reading Mama is like reading two interleaving books: one collection of vignettes painting a glorious picture of Antonella Gambotto-Burke’s ineffable love for her daughter; and one collection of essays and interviews about parenting in the modern world. There is only the most tenuous connection between the two.

Taking them separately, the vignettes form a profound tribute to love of her family, with whimsical stories of moments when her daughter has made her proud; but also dark tales of her own childhood, displaying a deep resentment of her own emotionally absent parents. The link between the two books, such as it is, is the attempt to explore and understand her own experiences of mothering and being mothered, in the context of the pressures of today’s society. She has learned from her own mother that motherhood has little value in itself, and honestly reports on her realisation of the importance of the slow pace of parenting, that the little things: “kissing, nursing, coddling, caring,” (p60) are really not so little; and yet are perceived by society to be low priorities.

The thesis of the second book is that this society is broken when it comes to parenthood, in that nobody other than a few select parents actually value or appreciate what parenting is, and how it works. This is supported with reference to literature, and interviews with a number of experts who generally make strong statements about how parents (as a generic group) are getting it wrong. Presumably excluding themselves, they largely see parents as a feckless, economically-driven crowd, so welded to their smartphones that they are unable and unwilling to give their children the proper amount of attention. This dysfunctionality is blamed for a range of social and mental health disorders from autism to AGB’s brother’s suicide. There is much handwringing over examples of parenting that have been witnessed by AGB and her interviewees.

Some of the interviewees unfold coherent and interesting arguments demonstrating the feminist nature of motherhood. Stephanie Coontz extends this to argue for the democratisation of care in general. This was the book that I wanted and expected to read, and I was frustrated by the much less coherent inclusion for example of the slow chapter on slow living, and the absolutely harrowing chapter about IVF. Some of the conversations, however, explore the strange and fallacious idea that the world is an unhealthy place, “toxic to children,” (p100), as if there was a time when all childhood was blissful and perfect. Perhaps this was the 1970s; I’m fairly certain that for most of the existence of humanity, children have had to muddle along with the rest of us, taking greater responsibilities at a younger age, subject to real hardship. When the focus shifts to fatherhood, AGB accuses men of “vanishing” (p178) from their children’s lives, yet when in history have fathers been expected to be more hands-on? Steve Biddulph on p83 claims that the children of hunter-gatherers were smarter; how can he possibly know this? And how are modern children even comparable to those whose life expectance was a fraction of ours? Modern concepts of attachment parenting are a very different thing.

AGB is an intelligent writer, and she has had access to some big names in parenting and child psychology. Her feminism rings loud and clear through this book; this is her manifesto for a society that recognises the contribution of mothers. Without the anecdotal chapters, it would be a very earnest book, making some fairly controversial points. Perhaps controversy is necessary to kick-start this important conversation.

After a final chapter on the nature of marriage and what it means to her (a dogmatic view that only marriage – not cohabiting – can facilitate continuity and commitment), AGB bravely completes the book with a heartbreaking epilogue about the horribly ironic end of her own marriage, which must have broken down even as she was writing about her love for her husband. It is hard to read, after some of her strong words (supported by several of her interviewees) about couples not making enough effort to stay together for the sake of their children, and the contribution of divorce to the dysfunctional disconnectedness of society. One wonders where she can go from here, in her thinking and her writing.

Mama presents some important ideas, though none of them are particularly new. I am frustrated and conflicted by this book, which comes out of a deeply personal self-exploration: AGB’s discovery that motherhood should not, after all, be a lesser status; and her shock that the rest of society has not yet figured this out. Because the state of motherhood does include vulnerability, and sacrifice, and menial work; but that does not mean that it wrecks our lives or that we are lesser people for doing it. In many ways, the motherhood she discovered lives up to her own expectations, but she is able to recognise the strengths that mothers must find to fulfil this role in the face of society’s judgement, and the lack of support from the community:

“At the most vulnerable time of their lives, mothers are repeatedly failed by the community.” (p24)

This disconnected, tech-obsessed world is the one we have, and I would rather read a manifesto for the future than a polemic moan about the state of the present, suffused with nostalgia for a rose-tinted past. This is an interesting, challenging read, which left me with much to reflect on.

[Disclosure: I was sent a free review copy of Mama by the publishers Pinter & Martin]

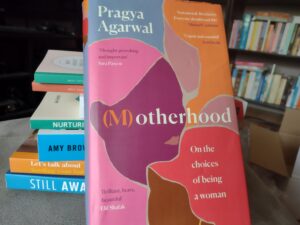

In a note at the end of the book, Pragya Agarwal accurately describes this work as “somewhere between a memoir and a scientific and historical disquisition of women’s reproductive choices and infertility.” (p343) Throughout the book she wanders, with intent, between her own reflections and experiences, and a huge breadth of culture, history, and contemporary research, to explore the massive topic of motherhood and choice, and to wrestle with the impossible definition of woman, and its relationship to motherhood.

In a note at the end of the book, Pragya Agarwal accurately describes this work as “somewhere between a memoir and a scientific and historical disquisition of women’s reproductive choices and infertility.” (p343) Throughout the book she wanders, with intent, between her own reflections and experiences, and a huge breadth of culture, history, and contemporary research, to explore the massive topic of motherhood and choice, and to wrestle with the impossible definition of woman, and its relationship to motherhood.