Relly is a writer, speaker and web content person. She lives in the Home Counties with her husband and their two small sons. As a result she thrives on country air and can be guaranteed to stand on Lego at least once a day.

I have a good life. I have a nice house which I rent. I have a good husband who I have been with for over ten years and 8.5 of them as a married couple. I have two amazing little boys who have both enthralled us and worn us to a nub for the last 6.5 years. I have a good brain that writes cool stuff for people, sometimes even for money.

I also have depression. I’ve had that longer than anything, around 17 years now, like the manky old sweatshirt that ends up in the back of your drawers – even though you’re sure you chucked it out last century.

I have seen depression described as a black dog, and a great comic book illustrating it as such, but for me a dog would be a comfort compared to depression. Depression, to me, is a dead weight that you must lug around from room to room, job to job, relationship to relationship. It feeds on you and your inner fears about yourself.

When my first son was born I had post-natal depression. I went to the doctor, practically dragged by my husband, two weeks after the birth and told him I was upset because our sink wasn’t working properly. The house was a mess after the baby. I was still heavy with milk and the midwife said I could get something to help with my sore skin. He listened to all this, with his head cocked to one side, and let me trail off to silence after I was done telling the carpet under my gaze all about my material concerns.

I looked up briefly. He asked me if I had bonded with my baby. I looked at the 7lb bundle sleeping jerkily in his carseat, fourteen days into our lifelong relationship. I was convinced I was not good for him. I was convinced I wasn’t even adequate. My husband was the most stressed I’d ever seen him. My body was an uncontrollable, lurching, leaking disaster after an emergency caesarean. My baby was uncomfortable drinking my milk, drinking formula, drinking reflux formula.

“No.” I said in a shaky whisper. “I want to give him away. I am not a good mother.”

I had fed my baby, rocked his crib for hours, researched ways to help him with his reflux, dressed him, changed him. But I hated holding him. If I picked him up he puked on me. Every time. So, I stopped. I sat at an arm’s length distance to him for around 72 hours. I tried to imagine telling everyone that I was giving him up for adoption – my husband, my parents, my inlaws. I realised that was not going to work. I started to plan running away but I had nowhere to go, and I was still so, so tired from the birth and everything after.

Then I stared at wall for three hours straight and wondered about suicide. I didn’t really feel suicidal but it did seem like a solution that meant both my husband and my baby were off the hook. These two people that I was not actually worthy of, who were being severely hindered by me. My husband made a doctor’s appointment for me during my three hours of quiet contemplation (I’m sure I was meant to have been napping really). I agreed to go because my husband asked me.

Two weeks later, I got offered a talking therapy session with a local counselor. I was really not into this at all but I went because, well, because the look in my husband’s eyes when he looked at me was breaking my heart. I attended a 35 minute ‘introductory’ session. The chap was very miffed that I’d brought my 4 week old newborn (who I was still part-breastfeeding), listened to me talk for a bit, asked if I was sleeping well (I remember my husband and I looked at each other for a moment with a look of despair – we had a four-week old baby, who was the only person getting any sleep round here!), and then declared I was not depressed – just ‘a bit of a worrier’ and I’d feel better when the baby slept.

We left the session. I cried a bit in the car park. I then refused to see anyone else for four months. I pretty much holed myself up in my house, bar trips outside to get nappies and milk if we ran out, and started running headlong into getting back into work of some sort. Our baby went to a childminder two afternoons a week so I could do baby-free chores and tasks, which was actually great for him and me, and this kept me buoyant (or at least in denial) for another couple of months. I was taking care of this baby. At some point, everyone would realise I wasn’t a good mother and then I’d be okay.

Except of course, inevitably, I did fall in love with him. He was my baby. We bonded. And then I was terrified. Terrified that people would realise I was inadequate. That I couldn’t face rhyme time at the library or making purees. That I hated NCT groups and mummy dates and baby swimming. My favourite days were the ones I’d pack him in his buggy and we’d take a train ride somewhere and I’d walk round parks and shops having to talk to no-one, save asking to use the baby change facilities. I could soak up human contact and conversation without having to be properly social. No-one would know I was an inadequate mother if I didn’t spend time with any other mothers.

That’s what depression does. It takes something that should be joyous and challenging and full of discoveries, and turns it into a time of loneliness, fear and a desperate feeling of not being good enough. Of shredding every last ounce of self-esteem and self-respect. It turns you into your worst enemy. It feeds off your inner self doubt.

Eventually, I cracked. I was so tired and so withdrawn and so miserable that when baby turned five months old, I cried for a week solid. My husband had to stay off work just to get me to eat, sleep and wash – and, of course, the baby needed the same things. I would be asleep from 3am-3pm, and then on the sofa as a burrito of misery, wrapped in my duvet and eating a single yoghurt, watching cbeebies and hating all the happy mothers and children.

My husband took me back to the doctors. This time they skipped the talking therapy preliminaries and prescribed an anti-depressant. It had some interesting side-effects – like yawning every three minutes, for five days – but it started to work. I began to come back to a more normal timetable, and a more stable mood. When I stopped crying, I realised that I was still as tired as the day after I’d given birth even though my baby was now a pretty good sleeper. I could barely lift my son in his car seat now. I went back to the doctors.

I had some blood work done and was told to call for the results in a week. The next day I had a message from my surgery, asking me to make an appointment urgently. I attended evening surgery. My thyroid had all but given up, probably in pregnancy, and I needed to take a thryoxine replacement immediately. For me, this was the last piece in the puzzle. The thryoxine and the anti-depressants worked together and I finally felt human again. Still vulnerable, still full of self-doubt – once you begin the self-sabotage of the depressive mindset it does not shake off easily – but getting better.

This story doesn’t have a ‘happy’ ending because, well, depression is a condition that has a habit of turning up and wrecking the kitchen at a party. But I made it through that time. Most people I met, not that I actively sought many out, would not have thought ‘that is a depressed person’ because if I was out of the door, I was able to wear my happy face that day.

And that’s still how it is today. Even if I’m feeling terrible, I personally can usually wear my happy face for a day or two – for important events, like my own wedding day(the year before my wedding I was heaving around the dead weight of undiagnosed depression) . The thing is, I pay for it later on. I usually get physically sick with an infection or virus, that forces me to stay inside and take up the duvet burrito position again. Sometimes I tumble down a metaphorical deep dark stairwell head first into misery.

Mostly I end up self-sabotaging – which is a bit like self-harming but instead involves somehow contriving to bring down your standard of work/output/creativity etc to somewhere around the murky mire depression would have you believe it exists. When I have days like this I am very conscientious not to charge my clients for work, which means I am both poorer than I should be and also sometimes miss deadlines. When I finally worked this out, therapy suddenly seemed both encouraging and financially cheaper than the alternatives.

I have recently started psychoanlaytical and cognitive behaviourial combined therapies to tackle the issues I have hanging over me from depression and its aspects as a mental illness. I describe myself as a broken doll to my boys, and they understand – at least a little – that Mummy is sometimes sick and that can make her not very happy.

If you are/ or think you might be depressed, or know someone that is, it does get better, mostly, for at least a while – and then you might slip and you have to haul yourself up again. You think you’re alone but so many of us are struggling and existing and improving and slipping and improving again. Screw up all your courage and put out your hand for help. Let someone catch hold of you.

Relly’s original post can be found here.

Get support:

Samaritans

NCT Information Sheet: Postnatal Depression

NCT Shared Experiences Helpline

Facebook: Berkshire Postnatal Support Group

House of Light Postnatal Depression Help

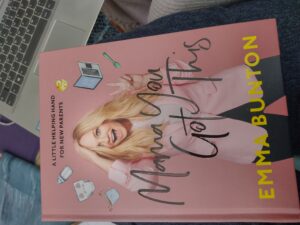

Mama, you’ve got this is the latest celebrity parenting book, from the pen of Spice Girl Emma Bunton and her team of experts. Emma has her own range of eco-disposable nappies to sell, alongside her advice for the first 12 months of parenthood.

Mama, you’ve got this is the latest celebrity parenting book, from the pen of Spice Girl Emma Bunton and her team of experts. Emma has her own range of eco-disposable nappies to sell, alongside her advice for the first 12 months of parenthood.