This book has come across my radar a few times, so I finally got round to picking up a copy. I think my lateness to the Emily Oster party may be because I didn’t much enjoy Linda Geddes’ similar book Bumpology, so let’s put that one to bed straight away; this is much, much better than Bumpology.

Expecting Better is well written, with a personal but not annoyingly chatty tone, while also explaining very clearly how to understand some quite complex research, and incorporate that into one’s decision making. It is aimed at parents-to-be and its chronology starts with trying to conceive, and to my disappointment ends at the birth, although I now see that there is a follow up, cleverly named Crib Sheets, which I shall be purchasing as soon as I finish typing this.

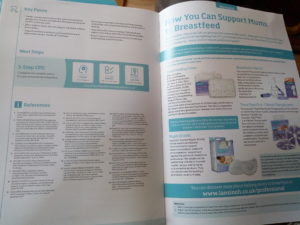

The consequence of the book ending with the birth of Oster’s daughter is that I cannot apply my usual test, of checking the tone and accuracy of the breastfeeding section. I have had, instead, to apply my more shallow knowledge of pregnancy and birth, to decide how good I think Expecting Better is.

Oster uses her introduction to explain that, as she is an economist by trade, she likes to make decisions using data. Her model of decision making is to take the data, and combine it with your own personal set of pros and cons. This, then, is how she has set out her book; and while it would be impossible for her to have researched every possible issue that a pregnant woman might face, it’s clear that she has written mainly about those decisions that she personally had to make. So we get almost an entire chapter on caffeine, and two paragraphs on restricted growth and related decisions. However, that is not to say that she doesn’t cover enough; the book is comprehensive, obviously well-researched, and thoroughly referenced., and key points are summarised at the end of each section for when you don’t feel like reading every nuance of the different antenatal screening options.

Language and some content has been edited for UK publication, however Oster is in the USA and this does skew some of what she feels she needs to know about, and her general attitude to birth. She touches on the role of midwives, but knows that a doctor (and a doula – hooray!) will be present at her birth, and she will certainly not be allowed to eat during her labour. The research she looks at are mostly USA, UK, Australian and European, with some cultural comparison as well. The induction methods discussed are definitely american, and there is limited discussion of any pain management options other than epidural.

The implicit message of this book is that informed consent is not possible for the majority of parents-to-be, as the necessary information is not easily accessible. Oster clearly makes up her own mind on a number of issues, after being given scant or even incorrect information by her own healthcare professionals; interestingly she doesn’t seem to question routine vaginal examination, and she is certainly working from an all-that-matters-is-a-healthy-baby point of view.

I sound critical but I did enjoy this book, learned some interesting things about caffeine, and was reminded that I haven’t read so much detailed information on food poisoning since I took my Intermediate Food Hygiene certificate, a quarter of a century ago. Emily Oster is a one-woman systematic review, driven by her own need for evidence to support her decision making; and the book she has produced will undoubtedly be useful for other parents, albeit with the caveat about some of the information being less applicable in the UK.

In a note at the end of the book, Pragya Agarwal accurately describes this work as “somewhere between a memoir and a scientific and historical disquisition of women’s reproductive choices and infertility.” (p343) Throughout the book she wanders, with intent, between her own reflections and experiences, and a huge breadth of culture, history, and contemporary research, to explore the massive topic of motherhood and choice, and to wrestle with the impossible definition of woman, and its relationship to motherhood.

In a note at the end of the book, Pragya Agarwal accurately describes this work as “somewhere between a memoir and a scientific and historical disquisition of women’s reproductive choices and infertility.” (p343) Throughout the book she wanders, with intent, between her own reflections and experiences, and a huge breadth of culture, history, and contemporary research, to explore the massive topic of motherhood and choice, and to wrestle with the impossible definition of woman, and its relationship to motherhood.